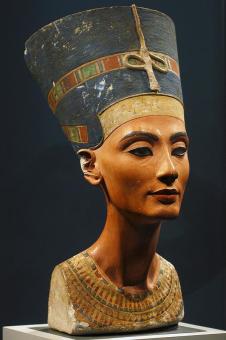

Finding Nefertiti

Could the mummy of the ancient Egyptian Queen Nefertiti, wife of the Pharaoh Akhenaten, finally have been identified, asks Nevine El-Aref from Al-Ahram Weekly

Photo by: REUTERS/Fabrizio Bensch

The beautiful Queen Nefertiti, wife of the monotheistic king Akhenaten, has always perplexed archaeologists.Nefertiti acquired unprecedented power during the first 12 years of the reign of her husband, and she occupied the throne alongside him and appeared nearly twice as often in reliefs as Akhenaten during the first five years of his reign. She continued to appear in reliefs even when, in the 12th year of Akhenaten’s reign, she disappeared from the scene and her name vanished from the pages of history.

Some think she either died from plague or fell out of favor, but recent theories have denied such claims. Four images of Nefertiti adorn Akhenaten’s sarcophagus, not the usual goddesses, indicating that her importance to the pharaoh continued up until his death and disproving the idea that she fell out of favor. They also show her continuous role as a deity or semi-deity with Akhenaten.

Shortly after her disappearance, Akhenaten took a co-regent to the throne. The identity of this person has created speculation. One theory says it was Nefertiti herself in a new guise as a “female king,” like the female Pharaohs Sobkneferu and Hatshepsut who ruled the country for several years.Another theory introduces the idea of two co-regents, a male one called Smenkhkare and Nefertiti under the name of Neferneferuaten. Some scholars believe that Nefertiti became co-regent with her husband and that her role as queen consort was taken over by her eldest daughter Meritaten.

Although her iconic bust, now on display at the Neues Museum in Berlin, was unearthed in an artist’s workshop at Tel Al-Amarna in 1912 by German archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt, neither her tomb nor her mummy have yet been unearthed.

Back in 1898, French Egyptologist Victor Loret excavated the tomb of Amenhotep II in the Theban Necropolis and came upon a remarkable find. This was the first tomb ever opened in which the pharaoh was still in his original resting place, and, moreover, 11 other mummies were also discovered in a sealed chamber in the tomb, nine belonging to members of the royal family.

Eight of the mummies were transferred to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, and three were left in site due to their critical state of preservation. One of this trio of mummies is a female who had managed to retain her remarkable beauty and is known among Egyptologists as the “Elder Lady”. She was identified as queen Tiye, the chief wife of the Pharaoh Amenhotep III.

A mummy of a young prince, not identified, bears a facial resemblance to that of Tiye’s mummy, suggesting it could be prince Thutmose, the eldest son of Amenhotep III. As for the third mummy, known as the “Younger Lady”, Egyptologists sway between thinking it is queen Nefertiti and princess Sitamun, a daughter of Tiye and Amenhotep III. Research was carried out at an early stage to verify whether the mummy of the Younger Lady was, in fact, Nefertiti, but to no avail.

Over the years, scientists have tried to identify the mummy of Nefertiti and determine her real facial features through carrying out scientific and archaeological research or using technology. But all attempts have thus far failed and been considered as mere speculation.

Now, however, some historians believe Nefertiti has already been found and currently lies in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

In 2003, Joanne Fletcher, a mummification expert from the University of York in the UK, announced that she and her team may have identified the mummy of the queen, as she believes that Nefertiti’s mummy could be that of the Younger Lady. She based her conclusions on a number of factors, such as its similarity in physiognomy and the swan-like neck of the mummy that bears a resemblance to Nefertiti’s face as immortalized in the limestone bust in Berlin, a doubled-pierced ear lobe, which she claims was a rare fashion statement in ancient Egypt and that can clearly be seen in images of Nefertiti, and a shaven head and the impression of the tight-fitting brow-band worn by royalty. Fletcher’s hypothesis has not been accepted by many Egyptologists, however. The x-ray examination carried out on the mummy of the Younger Lady prior to Fletcher’s theory indicated that it was a 16-year-old girl, whereas Nefertiti is thought to have died in her 30s. Without comparative DNA studies, any speculation about the owner of the mummy is dubious.

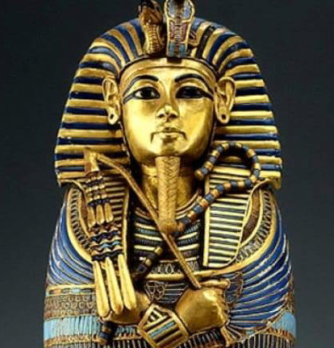

King Tut

In 2015, British Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves made headlines by announcing his belief that Nefertiti was buried in a secret chamber located behind the west and north walls of Tutankhamun’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings. But after three scan trials on the tomb’s walls the theory proved a failure, as well as receiving criticism from other Egyptologists and historians. Even so, it does demonstrate the enduring fascination with Nefertiti and finding her mummy.

New attempts: In an attempt to put an end to the Nefertiti mystery, the second phase of the Egyptian Mummies Project, whose first phase started in 2005 to solve the mystery of the death of the boy-king Tutankhamun, has resumed to study the rest of the royal mummies. The project will begin with those on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo before their relocation to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization (NMEC) in Fustat.

In September, a fresh search for Nefertiti’s mummy will begin. “We have prepared for such a search by the identification of two poorly preserved female mummies, one of them headless, found in 1870 by Italian explorer Giovanni Belzoni inside tomb KV21 in the Valley of the Kings in Luxor,” said former minister of antiquities Zahi Hawass. “Samples of fetuses found in the tomb of Tutankhamun were also taken for analysis,” Hawass told the Weekly, adding that these had long been thought to be the stillborn daughters of Tutankhamun and his royal wife Ankhesenamun, the daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti. “Comparison between their DNA and the headless mummy revealed that the headless KV21 mummy was in fact the mother of the two fetuses, which should mean that this was Tutankhamun’s wife queen Ankhesenamun,” Hawass said.

Queen Ankhesenamun, Tutankhamen wife

“I believe that the second female mummy in KV21 could be none other than queen Nefertiti,” Hawass said, explaining that the ancient Egyptians sometimes placed mother and daughter near each other in burial chambers. This was the case in tomb KV35, where the mummy of Tutankhamun’s grandmother queen Tiye was placed next to the mummy of one of Tiye’s many daughters, a woman revealed by DNA tests to be Tutankhamun’s mother. Hawass continued by saying that the Egyptian Mummies Project would also begin the search for other mummies that belonged to Nefertiti’s family, including her five other missing daughters and her sister queen Mutnodjmet in order to compare them with the second mummy without a head in KV21.

Source:

Al-Ahram Weekly is an English-language weekly broadsheet printed by the Al-Ahram Publishing House in Cairo, Egypt

Al-Ahram Weekly is an English-language weekly broadsheet printed by the Al-Ahram Publishing House in Cairo, Egypt